Ocean thermal energy conversion (OTEC) uses the temperature difference between cooler deep and warmer shallow or surface ocean waters to run a heat engine and produce useful work, usually in the form of electricity. OTEC is a base load electricity generation system, i.e. 24hrs/day all year long. However, since the temperature differential is small, the efficiency is low, decreasing the economic feasibility of ocean thermal energy for electricity generation.

Among ocean energy sources, OTEC is one of the continuously available renewable energy resources that could contribute to base-load power supply. The resource potential for OTEC is considered to be much larger than for other ocean energy forms [World Energy Council, 2000]. Up to 88,000 TWh/yr of power could be generated from OTEC without affecting the ocean’s thermal structure [Pelc and Fujita, 2002].

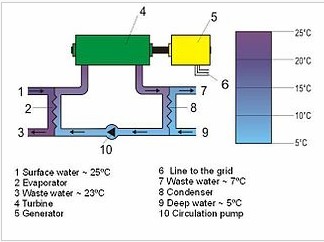

Systems may be either closed-cycle or open-cycle. Closed-cycle engines use working fluids that are typically thought of as refrigerants such as ammonia or R-134a. These fluids have low boiling points, and are therefore suitable for powering the system’s generator to generate electricity. The most commonly used heat cycle for OTEC to date is the Rankine cycle using a low-pressure turbine. Open-cycle engines use vapour from the seawater itself as the working fluid.

OTEC can also supply quantities of cold water as a by-product. This can be used for air conditioning and refrigeration and the nutrient-rich deep ocean water can feed biological technologies. Another by-product is fresh water distilled from the sea.

OTEC theory was first developed in the 1880s and the first bench size demonstration model was constructed in 1926. Currently the world’s only operating OTEC plant is in Japan, overseen by Saga University.

Working Principle

Cold seawater is an integral part of each of the three types of OTEC systems: closed-cycle, open-cycle, and hybrid. To operate, the cold seawater must be brought to the surface. The primary approaches are active pumping and desalination. Desalinating seawater near the sea floor lowers its density, which causes it to rise to the surface.

The alternative to costly pipes to bring condensing cold water to the surface is to pump vaporized low boiling point fluid into the depths to be condensed, thus reducing pumping volumes and reducing technical and environmental problems and lowering costs.

Closed – Closed-cycle systems use fluid with a low boiling point, such as ammonia (having a boiling point around -33 °C at atmospheric pressure), to power a turbine to generate electricity. Warm surface seawater is pumped through a heat exchanger to vaporize the fluid. The expanding vapor turns the turbo-generator. Cold water, pumped through a second heat exchanger, condenses the vapor into a liquid, which is then recycled through the system.

In 1979, the Natural Energy Laboratory and several private-sector partners developed the “mini OTEC” experiment, which achieved the first successful at-sea production of net electrical power from closed-cycle OTEC. The mini OTEC vessel was moored 1.5 miles (2.4 km) off the Hawaiian coast and produced enough net electricity to illuminate the ship’s light bulbs and run its computers and television.

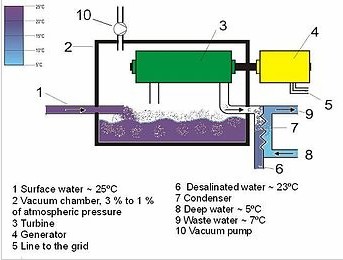

Open – Open-cycle OTEC uses warm surface water directly to make electricity. The warm seawater is first pumped into a low-pressure container, which causes it to boil. In some schemes, the expanding steam drives a low-pressure turbine attached to an electrical generator. The steam, which has left its salt and other contaminants in the low-pressure container, is pure fresh water. It is condensed into a liquid by exposure to cold temperatures from deep-ocean water. This method produces desalinized fresh water, suitable for drinking water, irrigation or aquaculture.

In other schemes, the rising steam is used in a gas lift technique of lifting water to significant heights. Depending on the embodiment, such steam lift pump techniques generate power from a hydroelectric turbine either before or after the pump is used.

In 1984, the Solar Energy Research Institute (now known as the National Renewable Energy Laboratory) developed a vertical-spout evaporator to convert warm seawater into low-pressure steam for open-cycle plants. Conversion efficiencies were as high as 97% for seawater-to-steam conversion (overall steam production would only be a few percent of the incoming water). In May 1993, an open-cycle OTEC plant at Keahole Point, Hawaii, produced close to 80 kW of electricity during a net power-producing experiment. This broke the record of 40 kW set by a Japanese system in 1982.

Hybrid – A hybrid cycle combines the features of the closed- and open-cycle systems. In a hybrid, warm seawater enters a vacuum chamber and is flash-evaporated, similar to the open-cycle evaporation process. The steam vaporizes the ammonia working fluid of a closed-cycle loop on the other side of an ammonia vaporizer. The vaporized fluid then drives a turbine to produce electricity. The steam condenses within the heat exchanger and provides desalinated water.

Working Fluids – A popular choice of working fluid is ammonia, which has superior transport properties, easy availability, and low cost. Ammonia, however, is toxic and flammable. Fluorinated carbons such as CFCs and HCFCs are not toxic or flammable, but they contribute to ozone layer depletion. Hydrocarbons too are good candidates, but they are highly flammable; in addition, this would create competition for use of them directly as fuels. The power plant size is dependent upon the vapor pressure of the working fluid. With increasing vapor pressure, the size of the turbine and heat exchangers decreases while the wall thickness of the pipe and heat exchangers increase to endure high pressure especially on the evaporator side.

Thermodynamics

A rigorous treatment of OTEC reveals that a 20 °C temperature difference will provide as much energy as a hydroelectric plant with 34 m head for the same volume of water flow. The low temperature difference means that water volumes must be very large to extract useful amounts of heat. A 100MW power plant would be expected to pump on the order of 12 million gallons (44,400 metric tonnes) per minute. For comparison, pumps must move a mass of water greater than the weight of the Battleship Bismark, which weighed 41,700 metric tons, every minute. This makes pumping a substantial parasitic drain on energy production in OTEC systems, with one Lockheed design consuming 19.55 MW in pumping costs for every 49.8 MW net electricity generated. For OTEC schemes using heat exchangers, to handle this volume of water the exchangers need to be enormous compared to those used in conventional thermal power generation plants, making them one of the most critical components due to their impact on overall efficiency. A 100 MW OTEC power plant would require 200 exchangers each larger than a 20-foot shipping container making them the single most expensive component

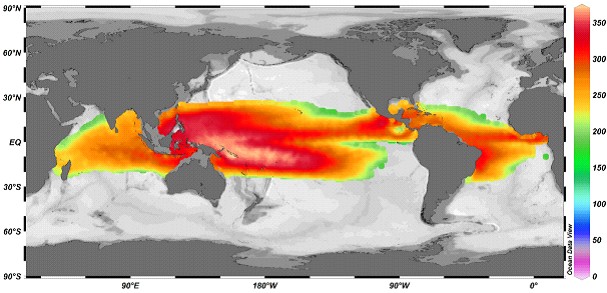

Since the intensity falls exponentially with depth y, heat absorption is concentrated at the top layers. Typically in the tropics, surface temperature values are in excess of 25 °C (77 °F), while at 1 kilometer (0.62 mi), the temperature is about 5–10 °C (41–50 °F). The warmer (and hence lighter) waters at the surface means there are no thermal convection currents. Due to the small temperature gradients, heat transfer by conduction is too low to equalize the temperatures. The ocean is thus both a practically infinite heat source and a practically infinite heat sink.

This temperature difference varies with latitude and season, with the maximum in tropical, subtropical and equatorial waters. Hence the tropics are generally the best OTEC locations.

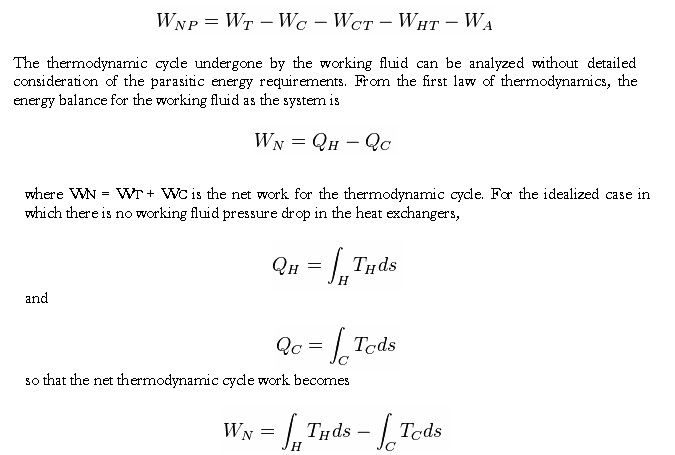

Closed Anderson cycle – It was developed in the 1960s by J. Hilbert Anderson of Sea Solar Power, Inc. In this cycle, QH is the heat transferred in the evaporator from the warm sea water to the working fluid. The working fluid exits the evaporator as a gas near its dew point.

The high-pressure, high-temperature gas then is expanded in the turbine to yield turbine work, WT. The working fluid is slightly superheated at the turbine exit and the turbine typically has an efficiency of 90% based on reversible, adiabatic expansion.

From the turbine exit, the working fluid enters the condenser where it rejects heat, -QC, to the cold sea water. The condensate is then compressed to the highest pressure in the cycle, requiring condensate pump work, WC. Thus, the Anderson closed cycle is a Rankine-type cycle similar to the conventional power plant steam cycle except that in the Anderson cycle the working fluid is never superheated more than a few degrees Fahrenheit. Owing to viscous effects, working fluid pressure drops in both the evaporator and the condenser. This pressure drop, which depends on the types of heat exchangers used, must be considered in final design calculations but is ignored here to simplify the analysis. Thus, the parasitic condensate pump work, WC, computed here will be lower than if the heat exchanger pressure drop was included. The major additional parasitic energy requirements in the OTEC plant are the cold water pump work, WCT, and the warm water pump work, WHT. Denoting all other parasitic energy requirements by WA, the net work from the OTEC plant, WNP is

Subcooled liquid enters the evaporator. Due to the heat exchange with warm sea water, evaporation takes place and usually superheated vapor leaves the evaporator. This vapor drives the turbine and the 2-phase mixture enters the condenser. Usually, the subcooled liquid leaves the condenser and finally, this liquid is pumped to the evaporator completing a cycle.

Efficiency of OTEC System

A heat engine gives greater efficiency when run with a large temperature difference. In the oceans the temperature difference between surface and deep water is greatest in the tropics, although still a modest 20 to 25 °C. It is therefore in the tropics that OTEC offers the greatest possibilities. OTEC has the potential to offer global amounts of energy that are 10 to 100 times greater than other ocean energy options such as wave power. OTEC plants can operate continuously providing a base load supply for an electrical power generation system.

The main technical challenge of OTEC is to generate significant amounts of power efficiently from small temperature differences. It is still considered an emerging technology. Early OTEC systems were 1 to 3 percent thermally efficient, well below the theoretical maximum 6 and 7 percent for this temperature difference. Modern designs allow performance approaching the theoretical maximum Carnot efficiency and the largest built in 1999 by the USA generated 250 kW.

Cost and economics

For OTEC to be viable as a power source, the technology must have tax and subsidy treatment similar to competing energy sources. Because OTEC systems have not yet been widely deployed, cost estimates are uncertain. One study estimates power generation costs as low as US $0.07 per kilowatt-hour, compared with $0.05 – $0.07 for subsidized wind systems.

Beneficial factors that should be taken into account include OTEC’s lack of waste products and fuel consumption, the area in which it is available, (often within 20° of the equator) the geopolitical effects of petroleum dependence, compatibility with alternate forms of ocean power such as wave energy, tidal energy and methane hydrates, and supplemental uses for the seawater.

Application of OTEC

OTEC has uses other than power production.

Desalination – Desalinated water can be produced in open- or hybrid-cycle plants using surface condensers to turn evaporated seawater into potable water. System analysis indicates that a 2-megawatt plant could produce about 4,300 cubic metres (150,000 cu ft) of desalinated water each day. Another system patented by Richard Bailey creates condensate water by regulating deep ocean water flow through surface condensers correlating with fluctuating dew-point temperatures. This condensation system uses no incremental energy and has no moving parts.

On March 22, 2015, Saga University opened a Flash-type desalination demonstration facility on Kumejima. This satellite of their Institute of Ocean Energy uses post-OTEC deep seawater from the Okinawa OTEC Demonstration Facility and raw surface seawater to produce desalinated water. Air is extracted from the closed system with a vacuum pump. When raw sea water is pumped into the flash chamber it boils, allowing pure steam to rise and the salt and remaining seawater to be removed. The steam is returned to liquid in a heat exchanger with cold post-OTEC deep seawater. The desalinated water can be used in hydrogen production or drinking water (if minerals are added).

Air conditioning – The 41 °F (5 °C) cold seawater made available by an OTEC system creates an opportunity to provide large amounts of cooling to industries and homes near the plant. The water can be used in chilled-water coils to provide air-conditioning for buildings. It is estimated that a pipe 1 foot (0.30 m) in diameter can deliver 4,700 gallons of water per minute. Water at 43 °F (6 °C) could provide more than enough air-conditioning for a large building. Operating 8,000 hours per year in lieu of electrical conditioning selling for 5-10¢ per kilowatt-hour, it would save $200,000-$400,000 in energy bills annually.

The InterContinental Resort and Thalasso-Spa on the island of Bora Bora uses an SWAC system to air-condition its buildings. The system passes seawater through a heat exchanger where it cools freshwater in a closed loop system. This freshwater is then pumped to buildings and directly cools the air.

In 2010, Copenhagen Energy opened a district cooling plant in Copenhagen, Denmark. The plant delivers cold seawater to commercial and industrial buildings, and has reduced electricity consumption by 80 percent. Ocean Thermal Energy Corporation (OTE) has designed a 9800-ton SDC system for a vacation resort in The Bahamas.

Chilled-soil agriculture – OTEC technology supports chilled-soil agriculture. When cold seawater flows through underground pipes, it chills the surrounding soil. The temperature difference between roots in the cool soil and leaves in the warm air allows plants that evolved in temperate climates to be grown in the subtropics. Dr. John P. Craven, Dr. Jack Davidson and Richard Bailey patented this process and demonstrated it at a research facility at the Natural Energy Laboratory of Hawaii Authority (NELHA). The research facility demonstrated that more than 100 different crops can be grown using this system. Many normally could not survive in Hawaii or at Keahole Point.

Japan has also been researching agricultural uses of Deep Sea Water since 2000 at the Okinawa Deep Sea Water Research Institute on Kume Island. The Kume Island facilities use regular water cooled by Deep Sea Water in a heat exchanger run through pipes in the ground to cool soil. Their techniques have developed an important resource for the island community as they now produce spinach, a winter vegetable, commercially year round. An expansion of the deep seawater agriculture facility is currently under construction next to the OTEC Demonstration Facility and will be completed in 2014.

Aquaculture – Aquaculture is the best-known byproduct, because it reduces the financial and energy costs of pumping large volumes of water from the deep ocean. Deep ocean water contains high concentrations of essential nutrients that are depleted in surface waters due to biological consumption. This “artificial upwelling” mimics the natural upwellings that are responsible for fertilizing and supporting the world’s largest marine ecosystems, and the largest densities of life on the planet.

Cold-water delicacies, such as salmon and lobster, thrive in this nutrient-rich, deep, seawater. Microalgae such as Spirulina, a health food supplement, also can be cultivated. Deep-ocean water can be combined with surface water to deliver water at an optimal temperature.

Non-native species such as salmon, lobster, abalone, trout, oysters, and clams can be raised in pools supplied by OTEC-pumped water. This extends the variety of fresh seafood products available for nearby markets. Such low-cost refrigeration can be used to maintain the quality of harvested fish, which deteriorate quickly in warm tropical regions. In Kona, Hawaii, aquaculture companies working with NELHA generate about $40 million annually, a significant portion of Hawaii’s GDP.

The NELHA plant established in 1993 produced an average of 7,000 gallons of freshwater per day. KOYO USA was established in 2002 to capitalize on this new economic opportunity. KOYO bottles the water produced by the NELHA plant in Hawaii. With the capacity to produce one million bottles of water every day, KOYO is now Hawaii’s biggest exporter with $140 million in sales.

Hydrogen production – Hydrogen can be produced via electrolysis using OTEC electricity. Generated steam with electrolyte compounds added to improve efficiency is a relatively pure medium for hydrogen production. OTEC can be scaled to generate large quantities of hydrogen. The main challenge is cost relative to other energy sources and fuels.

Mineral extraction – The ocean contains 57 trace elements in salts and other forms and dissolved in solution. In the past, most economic analyses concluded that mining the ocean for trace elements would be unprofitable, in part because of the energy required to pump the water. Mining generally targets minerals that occur in high concentrations, and can be extracted easily, such as magnesium. With OTEC plants supplying water, the only cost is for extraction. The Japanese investigated the possibility of extracting uranium and found developments in other technologies (especially materials sciences) were improving the prospects.

Global Development Of OTEC Plants

In numerically intensive simulations, the OTEC process is represented by a pair of sinks and a source of specified strengths placed at selected water depths across the oceanic region favorable for OTEC. Results broadly confirm earlier estimates obtained with a coarse (4 deg x 4 deg) OGCM, but with the greater resolution and more elaborate description of key physical oceanic mechanisms

The maximum global OTEC power production drops to 14 TW, or about half of previously estimated levels, but it would be achieved with only one-third as many OTEC systems.

Variation of yearly averaged OTEC power density (kW m-2)

As per MNRE, India, OTEC has a potential installed capacity of 180,000 MW in India.