System thinking is a method of critical thinking by which you analyze the relationships between the system’s parts in order to understand a situation for better decision-making. In simpler terms, you look at a lot of the trees, other plants and critters living around the trees, the weather, and how all these parts fit together in order to figure out the forest.

System thinking is a major departure from the old way of business decision-making in which you would break the system into parts and analyze the parts separately. Supporters of system thinking believe that the old way is inadequate for our dynamic world, where there are numerous interactions between the parts of a system, creating the reality of a situation. According to system thinking, if we examine the interactions of the parts in a system, we will see larger patterns emerge. By seeing the patterns, we can begin to understand how the system works. If the pattern is good for the organization, we can make decisions that reinforce it; but if the pattern is bad for the organization, we can make decisions that change the pattern.

Defining a System

First, we should begin by defining a system. A system is a set of parts that interact and affect each other, thereby creating a larger whole of a complex thing.

Let’s start with a simple example from nature: the Earth. Our planet is a very complex system consisting of atmosphere, water, mountains, plains, jungles, plants, insects, animals, humans, and our technological wonders, just to name a few. A scientist may look at many interactions of these parts in researching climate change. General patterns may be found in these interactions that may help explain the system and find solutions to the problems by changing the patterns of interaction between the parts.

Now, let’s apply the idea of a system to business. We’ll start small and work our way up. A business is a system consisting of many parts: employees, management, capital, equipment, and products, among others. Your business and your competitors comprise a system, which we may call an industry. Different industries – along with consumers, governments, and non-governmental organizations – make up our economic system. It can get even more complex, but we’ll stop here.

Systems Thinking Framework

The systems thinking framework below shows 3 inter-linked phases of any large-scale social change effort through a systems lens:

- Understanding the issue and the system(s) in which it lives, which includes inquiring deeply into how various beneficiaries and stakeholders experience the system

- Creating a plan for action by engaging system players around goals and assumptions, and looking together for points of leverage

- Learning and refining as you go by involving key stakeholders in an adaptive learning and sense-making process to discuss the “so what?” and “now what?” implications of what is being learned

Applying Systems Thinking

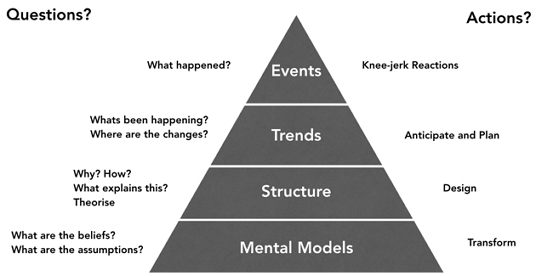

The iceberg model, is a structured way of observing and understanding systems and helps us think through complex problems and have the following benefits.

- Helps to move our focus away from events and symptoms toward structures, thinking and beliefs.

- Helps to develop shared thinking or “mental models” within teams and communities. This guides consistent and aligned action.

- Helps is to understand where leverage points are within the system. Those places where least effort produced maximum results.

A systems perspective is an effective means for helping leaders gain an understanding of the underlying structures, thinking and beliefs that shapes their organisations.

The first thing to notice about the “Iceberg Model” as illustrated above is that approximately two-thirds of an iceberg is under water, as the captain of the Titanic quickly discovered! The majority of the iceberg remains hidden from observation, beneath the water. This is true of the systems we interact with on a daily basis, much of the structure and thinking that produces their results remains hidden underwater.

The key to navigating and changing systems, is to see and understand the whole system. Not just that which can be easily observed, the events. Walking through the various layers of the iceberg following are some of the observations,

- Events – This is the surface level of the iceberg, usually we can easily see the “events” happening. Observable events answers the question ‘what happened?’ Linear thinking causes us to see the world as a series of events. This is not a bad way to see the world, however it does not provide a leveraged way to introduce change. A fixation on events often leads to attributing cause and effects in a superficial way, limiting our understanding and therefore our ability to introduce change.

- Trends and Patterns – As we string events together we begin to recognise trends and patterns, this provides a deeper level of understanding and along with it increased leverage, giving us a deeper level of insight; ‘this event has happened before’.

- Structure – After a trend or pattern is identified, the next step is to look for the dynamics that created the trend. There is some interpretation and theorising needed to develop and understand the structure. It requires that we develop a hypothesis as to what’s causing the trends. The structure creates the foundation, which supports the trends and patterns, resulting in events. Structure is important as it gives us a deeper understanding of the system and can help us to predict a systems behaviour.

- Mental Model – Systemic structures, in turn, are frequently held in place by the beliefs, perceptions, thinking or “mental models” – these beliefs are usually be undiscussable theories, residing in the minds of leaders, on what constitutes quality, service excellence or customer orientation. These beliefs may also affect interpersonal dynamics – such as approaches toward conflict, leadership or the best way to introduce change. Change the organisations thinking, beliefs and mental models and you change the organisations behaviour and results.

As we move down the iceberg we gain a deeper understanding of a system and at the same time gain increased leverage for intervening and changing the system and it’s results.

Using the iceberg model to guide us, we can ask probing questions, moving from the level of events down through the pyramid to the mental model level, as follows:

- Ask questions to identify key events: ‘What’s happening?’ or ‘What has happened?’

- Ask questions that surface patterns of trends: ‘Has this happened before?’ or ‘Is this problem similar to other’s we’ve had?’

- Ask questions that leads to the structure: ‘What structure is driving this problem?’ ‘Why do you think that?’ ‘What effect has the delay had?’ ‘What explains this?

Ask questions to understand belief systems and assumptions: ‘What is your understanding?’ ‘What are our beliefs about this?’ ‘What assumptions are we making and why?

Developing Systems Thinking

Various tools applied by leaders for developing systems thinking are,

Interconnectedness – Systems thinking requires a shift in mindset, away from linear to circular. The fundamental principle of this shift is that everything is interconnected. We talk about interconnectedness not in a spiritual way, but in a biological sciences way. Everything needs something else, often a complex array of other things, to survive.

Inanimate objects are also reliant on other things: a chair needs a tree to grow to provide its wood, and a cell phone needs electricity distribution to power it. So, when we say ‘everything is interconnected’ from a systems thinking perspective, we are defining a fundamental principle of life. From this, we can shift the way we see the world, from a linear, structured “mechanical worldview’ to a dynamic, chaotic, interconnected array of relationships and feedback loops.

A systems thinker uses this mindset to untangle and work within the complexity of life on Earth.

Synthesis – In general, synthesis refers to the combining of two or more things to create something new. When it comes to systems thinking, the goal is synthesis, as opposed to analysis, which is the dissection of complexity into manageable components. Analysis fits into the mechanical and reductionist worldview, where the world is broken down into parts.

But all systems are dynamic and often complex; thus, we need a more holistic approach to understanding phenomena. Synthesis is about understanding the whole and the parts at the same time, along with the relationships and the connections that make up the dynamics of the whole. Essentially, synthesis is the ability to see interconnectedness.

Emergence – From a systems perspective, we know that larger things emerge from smaller parts: emergence is the natural outcome of things coming together. In the most abstract sense, emergence describes the universal concept of how life emerges from individual biological elements in diverse and unique ways.

Emergence is the outcome of the synergies of the parts; it is about non-linearity and self-organization and we often use the term ‘emergence’ to describe the outcome of things interacting together.

A simple example of emergence is a snowflake. It forms out of environmental factors and biological elements. When the temperature is right, freezing water particles form in beautiful fractal patterns around a single molecule of matter, such as a speck of pollution, a spore, or even dead skin cells.

Feedback Loops – Since everything is interconnected, there are constant feedback loops and flows between elements of a system. We can observe, understand, and intervene in feedback loops once we understand their type and dynamics.

The two main types of feedback loops are reinforcing and balancing. What can be confusing is a reinforcing feedback loop is not usually a good thing. This happens when elements in a system reinforce more of the same, such as population growth or algae growing exponentially in a pond. In reinforcing loops, an abundance of one element can continually refine itself, which often leads to it taking over.

A balancing feedback loop, however, is where elements within the system balance things out. Nature basically got this down to a tee with the predator/prey situation — but if you take out too much of one animal from an ecosystem, the next thing you know, you have a population explosion of another, which is the other type of feedback — reinforcing.

Causality – Causality as a concept in systems thinking is really about being able to decipher the way things influence each other in a system. Understanding causality leads to a deeper perspective on agency, feedback loops, connections and relationships, which are all fundamental parts of systems mapping.

Systems Mapping – Systems mapping is one of the key tools of the systems thinker. There are many ways to map, from analog cluster mapping to complex digital feedback analysis. However, the fundamental principles and practices of systems mapping are universal. Identify and map the elements of ‘things’ within a system to understand how they interconnect, relate and act in a complex system, and from here, unique insights and discoveries can be used to develop interventions, shifts, or policy decisions that will dramatically change the system in the most effective way.