When people choose brands, they are not solely concerned with one single characteristic, nor do they have the mental agility to evaluate a multitude of brand attributes. Instead, only a few key issues guide choice.

In some of the early classic brands’ papers, our attention is drawn to people buying brands to satisfy functional and emotional needs. One has only to consider everyday purchasing to appreciate this. For example, there is little difference between the physical characteristics of bottled mineral water. Yet, due to the way advertising has reinforced particular positioning, Perrier is bought more for its ‘designer label’ appeal which enables consumers to express something about their upwardly mobile lifestyles. By contrast, some may buy Evian more from a consideration of its healthy connotations. If consumers solely evaluated brands on their functional capabilities, then the Halifax and Abbey National, with interest rates remarkably similar to other competitors, would not have such notable market shares in the deposit savings sector. Yet the different personalities represented by these financial institutions influence brand evaluation.

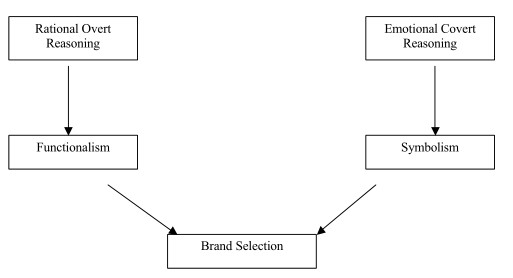

This idea of brands being characterized by two dimensions, the rational function and the emotionally symbolic, is encapsulated in the model of brand choice shown in Figure. When consumers choose between brands, they rationally consider practical issues about brands’ functional capabilities. At the same time, they evaluate different brands’ personalities, forming a view about them which fits the image they wish to be associated with. As many writers have noted, consumers are not just functionally orientated; their behavior is affected by their interpretation of brand symbolism. When two competing brands are perceived as being equally similar in terms of their physical capabilities, the brand that comes closest to matching and enhancing the consumer’s self concept will be chosen.

Components of Brand Choice – In terms of the functional aspects of brand evaluation and choice consumers assess the rational benefits they perceive from particular brand, along with preconceptions about efficacy, value for money, and availability. One of the components of functionalism is quality. For brands that are predominantly product-based Garvin’s work has shown that when consumers, rather than managers, assess quality they consider issues such as –

- Performance, for example the top speed of a car;

- Features-does the car comes with a CD stereo system as a standard fitting;

- Reliability-will the car starts first time every day it’s used;

- Conformance to specification- if the car is quoted to have particular petrol consumption when driving around town consumers expect this to be easily achieved;

- Durability, which is an issue Volvo majored on showing the long lifetime of its cars;

- Serviceability-whether the car can go 12 months between services;

- Aesthetics which Ford’s KA majored upon in its launch;

- Reputation consumers’ impressions of a particular car manufacturer.

At a more emotional level, the symbolic value of the brand is considered. Here, consumers are concerned with the brand’s ability to help make a statement about themselves, to help them interpret the people they meet, to reinforce membership of a particular social group, to communicate how they feel and to say something privately to themselves. They evaluate brands in terms of intuitive likes and dislikes and continually seek reassurances from the advertising and design that the chosen brand is the ‘right’ one for them.

Managers Brands Over Their Life Cycles

Different types of marketing activities are needed according to whether the brand is new to the market, or is a mature player in the market. In this section, we go through the main stages in brands’ life, cycles and consider some of the implications for marketing activity.

Developing and Launching New Brands

Traditional marketing theory, particularly that practiced by large fast moving consumer goods companies, argues for a well- researched new product development process. When new brands are launched, they arrive in a naked form, without a clear personality to act point of differentiation. Some brands are born being able to capitalize on the firm’s umbrella name, but even then they have to fight to establish their own unique personality. As such, in their early days, brands are more likely to succeed if they have a genuine functional advantage; there is no inherent goodwill, or strong brand personality, to act as a point of differentiation.

Marketers launching new technological brands need to adopt more practical approach, balancing the risk from only doing pragmatic, essential marketing research against the financial penalties of like laying a launch. The Japanese are masters at reducing risks with new technology launches with their so called ‘second fast strategy’ hey are only too aware of the cost of delays and once a competitor has a new brand on the market, if it is thought to have potential, they will rapidly develop a comparable brand.

There are several benefits from being first to launch a new brand in a new sector. Brands which are pioneers have the opportunity to gain greater understanding of the technology by moving up the learning curve faster than competitors. When competitors launch ‘me-too’ versions, the innovative leader should be thinking about launching next generation technology. Being first with a new brand that proves successful also presents opportunities to reduce costs due to economies of scale and the experience effect.

One of the nagging doubts marketers have when launching a new brand is that of the sustainability of the competitive advantage inherent in the new brand. The ‘fast-follower’ may quickly emulate the new brand and reduce its profitability by launching a lower-priced brand. In the very early days of the new brand the ways in which competitors might copy it are through –

- Design issues, such as color, shape, size;

- Physical performance issues, such as quality, reliability, durability;

- Product service issues, such as guarantees, installation, after sales service;

- Pricing;

- Availability through different channels;

- Promotions;

- Image of the producer

If the new brand is the result of the firm’s commitment to functional superiority, the design and performance characteristics, probably give the brand a clear differential advantage, but this will soon be surpassed. In areas like consumer electronics, a competitive lead of a few months is not unusual. Product service issues can sometimes be a more effective barrier. For example, BMW installed a software chip in their engines that senses, according to the individual are driving style, when the car needs servicing. Only BMW garages have the ability to reset the service indicator on their cars’ dashboards. Price can be easy to copy, particularly if the follower is a large company with a range of brands that they can use to support a short-term loss from pricing low. Unless the manufacturer has particularly good relationships with distributors that only stock their brand, which is not that common, distribution does not present a barrier to imitators.

Managing Brands during the Growth Phase – Once a firm has developed a new brand, it needs to ensure that it hall a view about how the brand’s image will be managed over time. The’ brand image is the consumers’ perceptions of who the brand is and what it stands for, i.e. it reflects the extent to which it satisfies consumers’ functional and representational needs.

At the launch, there must be a clear statement about the extension to which the brand will satisfy functional and representational needs. For example, Lego building bricks, when originally launched in 1960, were positioned as an unbreakable, safe toy, enabling children to enjoy creativity in designing and building

The original approach to supporting the representational component of the brand needs to be maintained as sales rise. For example for those brands that are bought predominantly to enable consumers to say something about themselves, it is important to maintain the self-concept and group membership associations. By communicating the brands positioning to both the target and non-target segments, but selectively working with distributors to make it diff! Cult for the non-targeted segment to buy the brand, its positioning will be strengthened –

Managing Brands during the Maturity – Phase In the maturity part of the life cycle, the brand will be under considerable pressure. Numerous competitors will all be trying to win greater consumer loyalty and more trade interest. One option is to extend the brand’s meaning to new products. A single image is then used to unite all the individual brand images.

Where the brand primarily satisfies consumers’ functional needs, these functional requirements should be identified and any further brand extension evaluated against this list to see if there is any similarity between the needs that the new brands will meet and those being satisfied by an existing brand. Where there is a link between the needs being satisfied by the existing brand and the new needs fulfilled by a new product. This represents an appropriate brand extension.

Managing Brands during the Decline Phase – As brand sales begin to decline, firms need to evaluate carefully the two main strategic options of recycling their brand or coping with decline.

When the brand is recycled the marketer needs to find new use for the brand, either through the functional dimension, or the representational dimension. A good example of functional brand recycling is the Boeing 727 aircraft. In the late 1960s, rising oil prices made this) aircraft less attractive to airline companies and sales fell. Boeing refused to let this brand die and redesigned the 727, making it moral economical on fuel. Sales of the brand recovered between 1971 and 1979with this functional improvement Guinness is a classic example of how a brand was repositioned to capitalize on demographic change, with marketing activity focusing on representational. Spearheaded by a novel promotional campaign, Guinness was sure successfully repositioned in the 1980s away from an ageing consumer group to younger drinkers.

Should the firm feel there is little scope for functional or representational brand changes, it still needs to manage its brands in the decline stage. If the firm is committed to frequent new brand launches, it does not want distributors rejecting new brands because part of the firm’s portfolio is selling too slowly. A decision needs to be taken about whether the brand should be quickly withdrawn, for example by cutting prices, or whether it should be allowed to die, gradually enabling the firm to reap higher profits through cutting marketing support.