Project Finance is the financing of the new construction or development of infrastructural and industrial projects. The financing is attained through both, public or private entities of the project and the debt is provided by a single bank, syndicate of banks or an investment group. Governments often participate to support the project in form of tax concessions and debt guarantee.

The debt provided is on a non-recourse (to the sponsors) or limited recourse basis, and repayment depends on the cash flow generated by the project when completed. Project financing needs significant investment at the beginning, and then the servicing of the debt is from the long-term cash flow. Hence, these types of loans have a longer maturity than straight-forward corporate lending.

From the viewpoint of the sponsor, the project needs to be able to satisfy the debt obligation and the annual profits generated by the project must be sufficient to pay back the capital investment within a reasonable time. The repayment should further add to the earnings of the company.

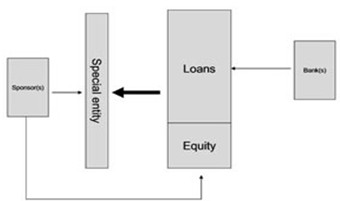

Figure: Project Finance Model

The industrial sectors where project financing is most often used are:

- Energy (power generation such as gas-fired, coal-fired, hydro, solar, wind or geothermal)

- Petroleum (upstream and downstream; pipeline construction)

- Natural gas (extraction and pipeline construction)

- Mining (coal, precious metals, metals, minerals)

- Chemical

- Telecommunications

- Maritime (port construction or redevelopment)

- Real estate

- Airports

- Transportation (road, bridge and tunnel; train / rail line for both public transport and industrial freight; rail stations)

- Water and sanitation / waste management

- Public health facilities

The benefit to the lender in financing a project is that it allows them to keep the project off of the company’s balance sheet. This protects the company from the failure of the project. There are instances where the company’s balance sheet does not have the strength to justify financing the project through corporate finance. However, lending corporations must perform a cost benefit analysis (capital investment vs. expected rate of return) of the project so that the project generates an annual net operating income equal to a specific percentage of the loan value before project finance is feasible. For efficient credit analysis, a manger must assess the following entities involved in the project i.e. the project feasibility study:

- Sponsor(s)

- Joint-ownership structure of the project.

- Host nation (or nations if the project crosses national boundaries).

- Project supervisor

- Contracts regarding construction, supply, off-take, maintenance and concession agreements

- Contractors and Subcontractors and any performance surety bond(s).

- Supplier (for instance, gas or coal delivery to a power plant).

- Potential customers for the project’s services once completed.

In the feasibility study, one must diligently carry out the assessment as some parties already tend to be predisposed to a specific location, design or outcome and may influence, directly or indirectly. The lenders must determine how much of the project to actually finance, which will be the debt-to-total capitalization ratio of the corporate entity that owns the project. This leverage could be as high as 70%. A project’s borrowing capacity should be based on the cash flow projections of the infrastructure once in operation. Lenders borrow the funds for the project (partly short-term), and therefore the timing and certainty of project cash flows is necessary for the lenders to manage their own balance sheet liabilities.

The non-recourse clause makes the lender(s) exposed to a project-specific/asset-specific credit risk. The risk can be controlled by:

- purchasing a credit derivative in the capital markets

- entering into a public-private partnership (PPP) with the host government

- obtaining an credit agency guarantee (which may result in lengthening the maturity of the loan)

- securitizing the loan.

Once the project is operational, the lender(s) may have to enter into a currency derivative product to shield themselves from any fluctuations in the value of the local currency cash flow.

Other pertinent questions/features to keep in mind during the feasibility study are:

- The level of experience of the sponsors and what is the level of experience of the operator of the facilities. The credit worthiness and financial strength must be evident to support the completion of the project.

- Lenders’ competency level, third-party auditor who can monitor the project on-site and provide accurate assessments.

- Budget/cost increases or construction delays increasing the original amount of the loan or resulted in a delay in the scheduled loan repayment.

- Proper control over the management of the project to free cash flows generated by the project operation for opportunistic or inefficient investments.

- Local supply of skilled labour to operate and maintain the facilities.

- Credit concentration in the project’s off-take agreement.

- The project’s right to sell excess capacity during periods when it is not needed to meet contractual wholesale/retail requirements.

- Issuance of any Revenue Bonds that are secured by a pledge of, and a lien on, a proportionate amount of the revenues of the electric system, after deducting operating expenses.

- Type of insurance, or self-insurance, is available for the operating entity’s casualty and property exposures.

- Cash streams in a foreign currency denomination or commodity inputs accurately hedged by specific derivative products/contracts.

The specific risks involved in funding large-scale projects and the key characteristics of project financing structures are:

- In this approach, the default risk underlying credit spreads is primarily driven by two components:

- the degree of firm indebtedness or leverage and

- the uncertainty about the value of the firm’s assets at maturity.

Taking into consideration the assumption of decreasing leverage ratios over time, delaying the maturity date decreases the probability that the value of the assets will be below the default boundary when repayment is due. On the other hand, a longer maturity also increases the uncertainty about the future value of the firm’s assets. For obligors that already start with low leverage levels, this second component dominates, so that the observed term structure is monotonically upward-sloping. For highly leveraged obligors, instead, the increase in default risk due to higher asset volatility will be strongly felt by debt holders at short maturities, but as maturity further increases, the first component will rapidly take over, thanks to the greater margin for risk reduction due to declining leverage. This leads to a hump-shaped term structure of credit spreads for highly leveraged obligors.

- Despite the extensive network of security arrangements, the credit risk of non-recourse debt remains ultimately tied to the timing of project cash flows. In fact, projects which are financially viable in the long run might face cash shortages in the short term. Ceteris paribus, obtaining credit at longer maturities implies smaller amortising debt repayments due in the early stages of the project. This would help to relax the project company’s liquidity constraints, thus reducing the risk of default. As a consequence, long-term project finance loans should be perceived as being less risky than shorter-term credits.

- Third, the credit risk of non-recourse debt might be affected not only by the timing but also by the uncertainty of project cash flows and how the latter evolves over the project’s advancement stages. In fact, successful completion of the construction and setup phases can significantly reduce residual sources of uncertainty for a project’s financial viability. Arguably, extending loan maturities for any additional year after the scheduled time for the project to be completely operational might drive up ex ante risk premia but only at a decreasing rate.

- The term structure of credit spreads observed in project finance is likely to be affected by the higher exposure of large infrastructure projects to political risk and by the availability of political risk insurance for long-term project finance loans. While long maturities and political risk represent in principle separate sources of uncertainty, commercial lenders are often willing to commit for longer maturities in emerging economies only if they obtain explicit or implicit guarantees from multilateral development banks or export credit agencies. As political risk guarantees are most often associated with longer maturities, lenders should not necessarily perceive political-risk-insured long-term loans as being riskier than uninsured short-term loans, ceteris paribus.