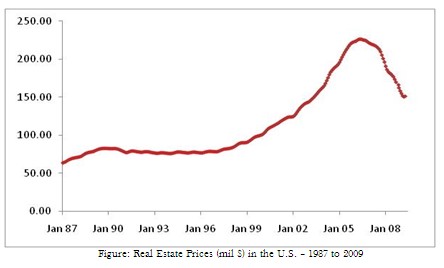

After the Great Depression in the 1930s, the world witnesses another significant crash in 2008. The downfall, caused by events of 2007 (sub-prime mortgages), effected the entire U.S. financial sector and then financial markets overseas.

The impacted parties in the United States were:

- the entire investment banking industry

- the insurance companies

- two enterprises chartered by the government to facilitate mortgage lending

- mortgage lenders

- the largest savings and loan

- commercial banks.

Companies that normally rely on credit, such as the auto industry, suffered heavily. Banks ceased lending money to businesses that need to regulate their cash flows and without which they cannot do business. Share prices plunged throughout the world—the Dow Jones Industrial Average in the U.S. lost 33.8% of its value in 2008—and by the end of the year, a deep recession had enveloped most of the globe. By the end of the year, Germany, Japan, and China were locked in recession, as were many smaller countries. Less-developed countries likewise lost markets abroad, and their foreign investment, on which they had depended for growth capital, withered.

In order to get the economy back on track, the Fed tried to reduce short-term interest rates, but this did not work. By the end of 2008, its target for the federal funds rate (which banks charge one another for overnight loans), was low within the range of 0–0.25%. The Fed then also tried other ways of injecting money into the economy, through:

- loans,

- loan guarantees, and

- purchases of government securities.

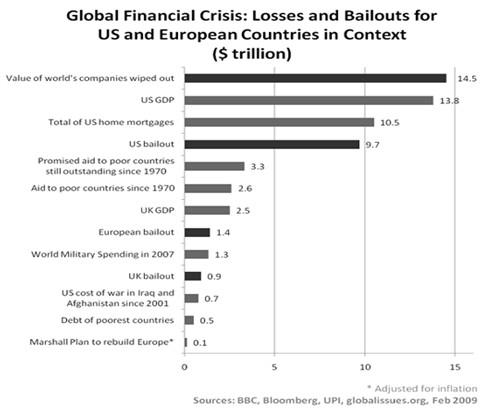

By December the Fed had spent more than $1 trillion into the economy.

Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson asked Congress to establish a $700 billion fund to keep the economy from seizing up permanently. The Treasury invested most of the newly authorized bailout fund directly into the banks that held the toxic securities (thus giving the government an ownership stake in private banks). This would enable the banks to resume lending. The Treasury’s stance appeared to open access to the bailout money to anyone suffering from the frozen credit markets. This was the basis for the auto manufacturers’ plea for a piece of the pie.

Still, all that money did little, at least at first, to stimulate private bank lending. Everyone with money to lend turned to the safest haven of all—Treasury securities. So popular were short-term Treasuries that investors in December bought $30 billion worth of four-week Treasury bills that paid no interest at all, and, very briefly, the market interest rate on three-month Treasuries was negative.

Barack Obama, who was elected in November to succeed President Bush as of Jan. 20, 2009, prepared a package of approximately $1 trillion in tax cuts and spending programs to stimulate economic activity.

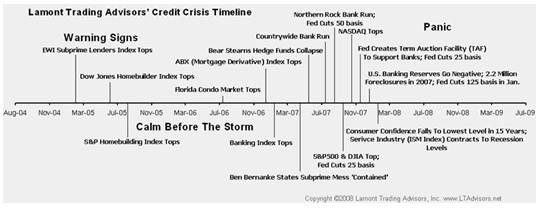

The timeline below represents the trail of events which took place before and after the crash until 2009.

International Repercussions

Although the financial crisis was conceived and spread in the US, the rest of the world was not spared from the impact.

- TheK. government provided $88 billion to buy banks completely or partially and promised to guarantee $438 billion in bank loans.

- The governments of the three Benelux countries—Belgium,The Netherlands, andLuxembourg—initially bought a 49% share in Fortis NV within their respective countries for $16.6 billion, though Belgium later sold most of its shares and The Netherlands nationalized the bank’s Dutch holdings.

- Germany’s federal government rescued a series of state-owned banks and approved a $10.9 billion recapitalization of Commerzbank. In the banking centre ofSwitzerland, the government took a 9% ownership stake in UBS.Credit Suisse raised funds from the government of Qatar and private investors.

- InGreece streetriots in December reflected, among other things, anger with economic stagnation.

- Iceland found itself near bankruptcy, withHungary andLatvia moving in the same direction. Iceland’s three largest banks had grown too large for their own good, with assets worth 10 times the entire country’s annual economic output. When the global crisis reached Iceland in October, the three banks collapsed under their own weight. The national government managed to take over their domestic branches, but it could not afford their foreign ones.

- Japan’s andChina’sexport-oriented industries suffered from consumer retrenchment in the S. and Europe. Compounding the damage, exporters could not find loans in the West to finance their sales. Japan, in the second quarter of 2008, ended with a 3.7% contraction at an annual rate, followed by 0.5% in the third quarter. China’s economy however continued to grow but not at the double-digit rates of recent years. Exports were actually lower in November than in the same month a year earlier, quite a change from October’s 19% increase. The government devised a 2-year $586 billion economic stimulus plan, and the central bank frequently cut interest rates.

As in the U.S., the financial crisis spilled into Europe’s overall economy. Germany’s economic output, the largest in Europe, contracted at annual rates of 0.4% in the second quarter and 0.5% in the third quarter. Output in the 15 euro zone countries shrank by 0.2% in each of the second and third quarters, marking the first recession since the euro’s debut in 1999.

The pressures of the financial crisis seemed to be forging more new alliances. Officials from Washington to Beijing coordinated interest rate cuts and fiscal stimulus packages. Top officials from China, Japan, and South Korea—long time adversaries—met in China and promised a cooperative response to the crisis. Top-level representatives of the Group of 20 (G-20)—a combination of the world’s richest countries and some of its fastest-growing—met in Washington in November to lay the groundwork for global collaboration. The G-20’s deliberations were necessarily tentative in light of the U.S. presidential transition in progress.

By year’s end, all of the world’s major economies were in recession or struggling to stay out of one. In the final four months of 2008, the U.S. lost nearly two million jobs. It forecast an increase in global economic output of just 0.9% in 2009, the most tepid growth rate since records became available in 1970. Measured by its impact on global economic output, the recession that had engulfed the world by the end of 2008 figured to be sharper than any other since the Great Depression.